Google Chrome Extension: Phishing Detector

Project Overview

For my Network Security class we were tasked with working on any project that dealt with web security, and given my background in A.I I decided to go with a Phishing detector as a google chrome extension. I am aware that phishing URL detection is one of the first A.I projects people do for their A.I classes, so I wanted to go beyond what is expected in that project. The main objective was to make this reliable in actual use rather than just to get an accuracy score from a dataset, this project should also be accurate in use, with the second objective being to actually make it functional as a google chrome extension.

Dataset and initial challenges

The A.I was trained on over 200,00+ URLS from UCI’s phishing dataset that came with labelled URLs and over 40 features that describe the URL and the contents of the page.

This immediately introduced the first challenge. Page content features are rarely present in traditional phishing training projects, and even then, they are only validated with a testing set which does not require a way to scrape page data for actual testing… since well… There is no actual testing for those projects. So to maximize the reliability of our algorithm, we had to implement a page scraper which helped the agent take into account another dimension of features.

“Brief” machine learning foundations

Features

So before we go deeper in this project, we need to explain what machine learning even is. Machine learning is an automated process that tries to figure out patterns in data to come to a conclusion on the classification. As for what patterns it’s looking at, that is determined by features. Let’s say we have a URL “www.google.com”, features of this URL would be:

- Character count

- Top-level domain (.com)

- Number of digits (Zero in this case).

You might be saying “Do numbers in a URL signify that it is a phishing site?” and “I’ve seen people fall for goog1e.com, so obviously numbers in URLs mean that it IS phishing!” That is some pretty good intuition, and you are right to assume that numbers could indicate phishing, but that isn’t always a given and we also need to reduce the amount of false positives we would be getting. So could we assume numbers make it more likely? Sure, there is no harm in thinking that, so how does a ML see the fact there are numbers in a URL and weigh it more towards it being phishing?

What if we had a feature that was a simple boolean value that indicated that the URL is similar to an existing one. What if that feature was triggered in tangent to the numbers detected feature? We can’t tell the AI to flag that automatically by hardcoding, it has to come to that conclusion on its own. It has to realize there’s a trend between those two features and it usually ends up with a certain label (A GIVEN value that states the “answer” of a data entry). There are a bunch of these connections between features, some which indicate it’s safe, some indicate it’s phishing, and some that are reliant on multiple other features.

| Category | Features |

|---|---|

| Basic URL Structure (12) | Url_length, domain_length, domain_name_length, tld_length, path_length, query_length, path_depth, character counts, has_file_extension, suspicious_file_ext, double_slash, trialing_slash, uses_http, uses_https |

| Domain Analysis (8) | Subdomain_count, has_subdomain, has_port, has_ip, has_suspicious_tld, has_numbers_in_domain, domain_entropy |

| Path Metrics(3) | Num_params, has_suspicious_params, query_length, path_length, path_depth, file extensions |

| Suspicious Patterns & Obfuscation (10) | Has_at_symbol, has_shortner, has_suspicious_keywords, has_obfuscation, num_obfuscated_chars, obfuscation_ratio, digit_ratio, letter_ratio, special_char_ratio, url_entropy |

| Brand Detection & Homograph (9) | Suspicious_brand_usage, brand_in_registered_domain, brand_in_subdomain, brand_in_path_or_query, brand_mismatch, brand_similairity_registered, brand_similarirty_subdomain, brand_similairity_path, brand_homograph |

| Category | Features |

|---|---|

| Content Structure (3) | LineOfCode, LargestLineLength, HasTitle |

| Title Matching (2) | DomainTitleMatchScore, URLTitleMatchScore |

| Trust Signals (4) | HasFavicon, Robots, IsResponsive, HasCopyRightInfo |

| Redirect Analysis (2) | NoOfURLRedirect, NoOfSelfRedirect |

| Metadata (1) | HasDescription |

| DOM Structure (2) | NoOfPopup, NoOfiFRame |

| Form Analysis (4) | HasExternalFormSubmit, HasSubmitButton, HasHiddenFields, HasPasswordField |

| Social Presence(1) | HasSocialNet |

| Keyword Detection (3) | Bank, Pay, Crypto |

| Resource Counts (3) | NoOfImage, NoOfCSS, NoOfJS |

| Link Analysis (3) | NoOfSelfRef, NoOfEmptyRef, NoOfExternalRef |

Random forest

Now is the perfect time to explain what a random forest tree algorithm is. We went over how an algorithm comes to a decision. Lets visualize that process as a flowchart where features determine the flow. These flowcharts are complex but what’s important to gather from this, is that a tree outputs a classification answer.

You might think I just described the ML process again but introduced new terminology. That is true, the only new concept to add here is that there are multiple of these trees, and the final conclusion is gathered by a majority vote stemming from thousands of trees. Each of those trees has its own configuration or “flow charts”. Combining these trees to come to a single conclusion is known as a random forest model.

Feature Engineering

So if we already have a dataset that has features extracted, what now? If you just want to get a 90% accuracy test, it’s actually quite easy because there are already packages that do the heavy work. So do we have to implement our own algorithms to get a higher score? Thankfully, no. What we should do is implement feature engineering by creating additional thoughtful features. The UCI dataset has a vast amount of reference URLs, all with thoughtful features already extracted. Large datasets and feature categories provide engineers with more accurate results. Running a premade ML package with the UCI dataset resulted in a 98% accuracy. The way it got that accuracy result is by training the ML with 85% of the dataset and testing it on the remaining 15%.

We could aim higher, but how? We can implement our own features, which might require some custom functions and new reference data. One of the features we implemented was a brand homograph boolean. Brand homographs are a cyberattack where threat actors replace certain characters with ones that appear visually similar, such as o and 0, or even more similar like using a latin ‘a’ and a Cyrillic ‘a’ (Which look identical!). Each url is cross referenced with a whitelist bank to check if a brand homograph is detected.

Other custom features were also implemented, such as typosquatting which are also similar urls but rely on the user mistyping a character or two (“www.google.com” vs “www.googel.com”). The implementation of custom features improved our accuracy testing score from 98% to 99.3%, which is more impactful than it seems, because those two attacks are more prominent in reality than the dataset implies.

| Feature | Importance |

|---|---|

| uses_https | 22.38% |

| uses_http | 19.32% |

| num_slashes | 12.48% |

| path_depth | 10.66% |

| digit_ratio | 3.96% |

| brand_similarity_subdomain | 3.93% |

| trailing_slash | 3.37% |

| url_length | 2.04% |

| Brand_similiarity_path | 1.90% |

Top Page Features

| Feature | Importance |

|---|---|

| NoOfExternalRef | 24.67% |

| NoOfSelfReg | 14.91% |

| NoOfImage | 13.15% |

| LineOfCode | 12.22% |

| NoOfJS | 8.44% |

| NoOfCSS | 6.22% |

| HasSocialNet | 5.68% |

| HasCopyRightInfo | 4.51% |

| HasDescription | 3.14% |

Browser Extension overview

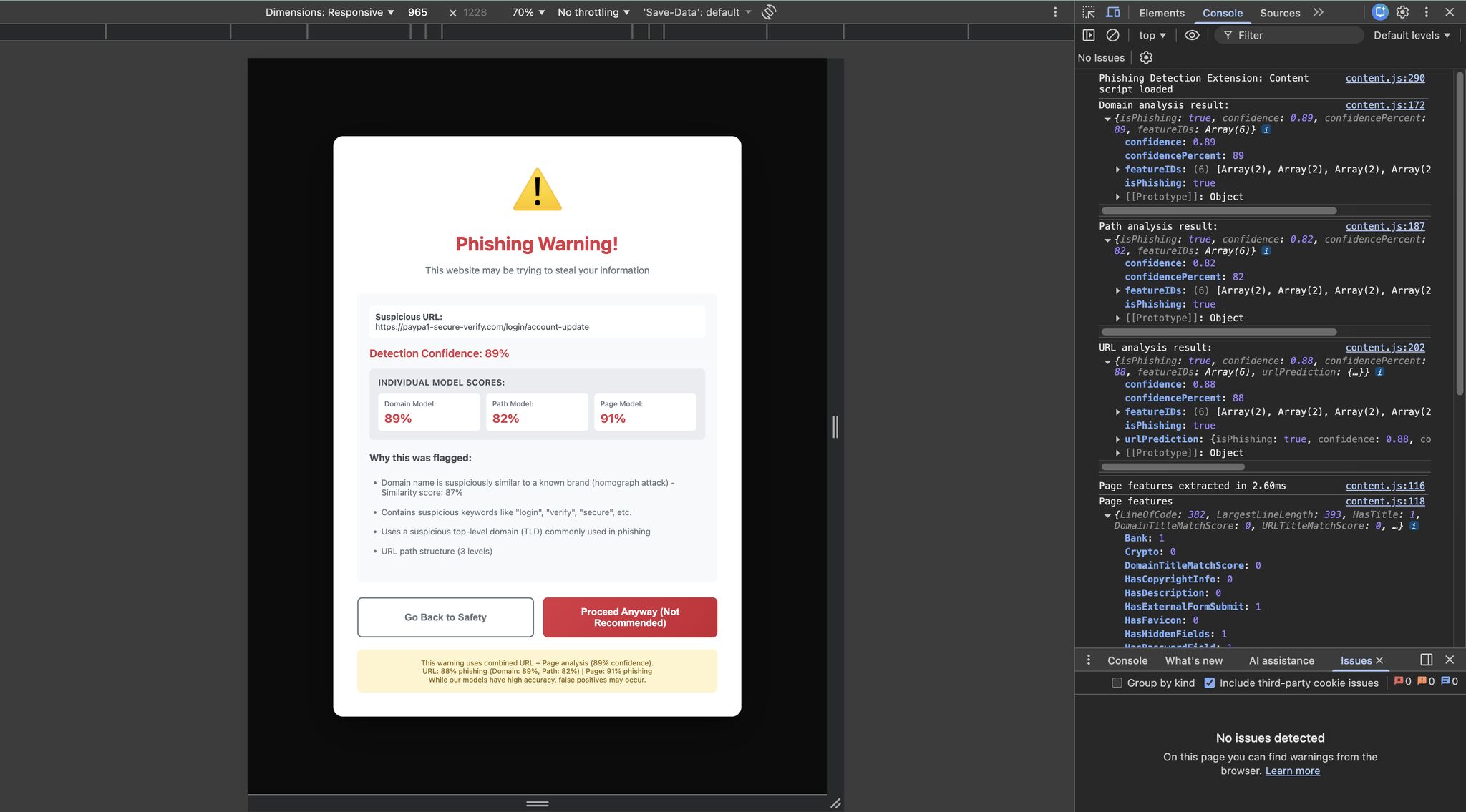

Before we go over the practical testing, let’s discuss the browser extension a bit. The extension stores the trees on the browser so the user does not need to communicate with a backend, making it so the average classification time is under 2ms. The extension also blocks the website and provides contextual-dependent analysis providing insight on why the website was flagged. There are some details present in the screenshot of the extension that might be confusing and will be explained later, but you deserve a picture to look at for making it this far.

For testing if our browser extension was configured properly, we turned off the page scraping features and tested some of the correctly identified URLs to see if they got the same results. Testing the extension gave us the expected results for the benign and malicious links (Which were thankfully taken down). For the page model, we tested our own websites to see if they would be flagged. The websites were made accurate to how actual phishing websites would be, by being vibe coded. We turned on page scraping and “Vibe coded” (as most phishing websites now are) a website that displayed features present in phishing websites and tried visiting them and as the above screenshot shows, the extension did catch it.

Path Model

You may have noticed in the screenshot that the extension displays multiple scores. We intentionally split the machine learning system into a URL model and a page model, each with different weightings. The reasoning behind this was simple: we believed the page model was comparatively underdeveloped due to limited feature coverage and scraping constraints, so it should not dominate the final decision.

That raises the obvious question: what about the third score, the path score? Why was that necessary? This is where relying purely on testing set accuracy becomes problematic for phishing detection. During evaluation, the model was flagging nearly 50% of URLs that contained paths (for example, google.com/account). At first, this was confusing. The dataset did contain URLs with paths, so why was this happening?

The issue was not the absence of paths, but the lack of variance in how paths appeared in the dataset. In real-world browsing, URL paths are often messy and unpredictable. They commonly include UUIDs or other identifiers tied to resources or user sessions, especially once you move beyond a homepage. A familiar example is logging into platforms like Canvas or Blackboard, where the full URL contains long, seemingly random strings. These randomized strings unintentionally triggered one of our features that measures how “random” a URL appears. Disabling that feature entirely was an option, but it had proven valuable during training, so removing it would have weakened the model elsewhere.

Instead, we introduced a separate path model with its own feature set. Only the domain is evaluated by the URL model (now more accurately referred to as the domain model), while the path is analyzed independently. This separation significantly reduced false positives, dropping them from roughly 50% to about 2%. While a 2% false-positive rate would still be problematic for a production system, this was a reasonable tradeoff given the scope and time constraints of a class project. With this adjustment, the final testing accuracy improved to 99.64%, effectively cutting the remaining error rate in half.

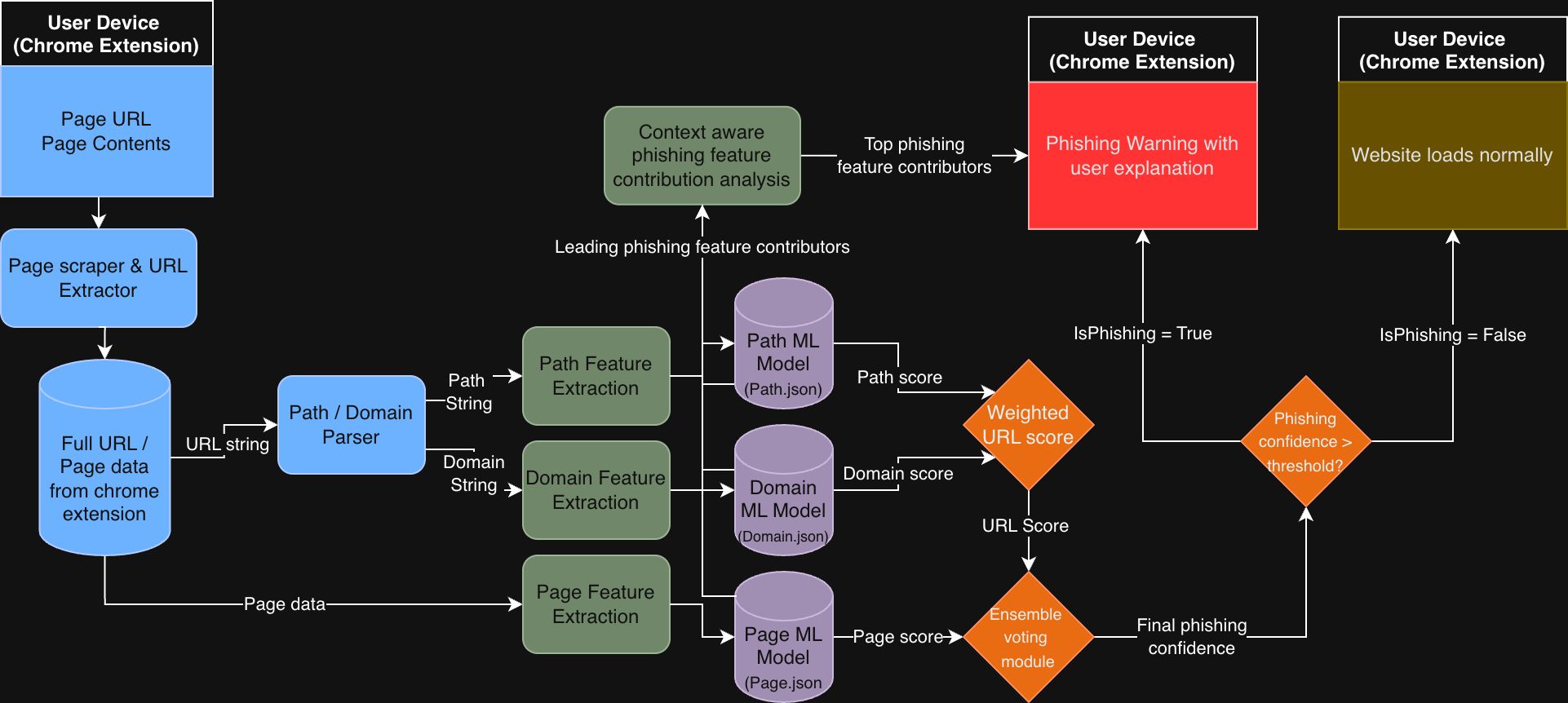

System Architecture & Model Performance

The figure above illustrates the full end-to-end architecture of the phishing detection system as deployed in the Chrome extension. All processing occurs locally on the user’s device. The extension captures the page URL and page content, performs feature extraction for the domain, path, and page content, and feeds each feature set into its corresponding machine learning model. Each model produces an independent score, which is then combined through a weighted ensemble voting mechanism to generate a final phishing confidence score. If this confidence exceeds a predefined threshold, the extension blocks the page and presents a phishing warning along with a context-aware explanation highlighting the most influential features that contributed to the decision. Otherwise, the site is allowed to load normally.

To wrap it all up, here is the system architecture of this project.

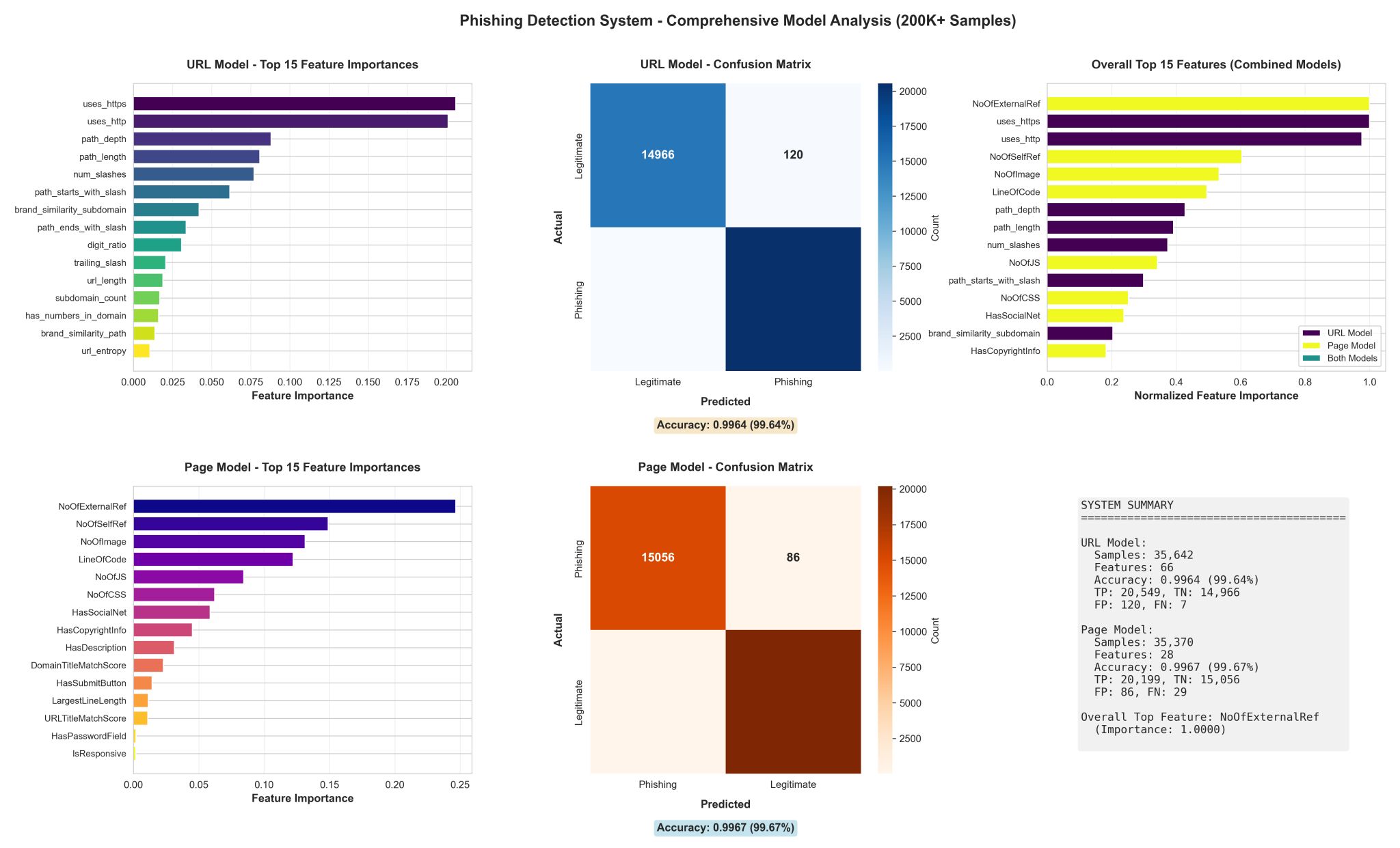

The performance results and feature importance analyses are shown above. The URL (domain) and page models were evaluated independently, each achieving accuracy above 99.6%, with confusion matrices indicating very low false positive and false negative rates. Feature importance rankings further validate that the models learned meaningful signals rather than overfitting to noise. On the URL side, HTTPS usage, path depth, slash count, digit ratio, and brand similarity indicators emerged as dominant contributors. For the page model, structural and behavioral features such as external references, self-references, resource counts, and page complexity played a significant role.

When combined, the ensemble system achieved a final testing accuracy of 99.64%, while substantially reducing false positives caused by high-variance URL paths. More importantly, these results aligned with real-world phishing behavior rather than relying solely on dataset-specific patterns, reinforcing the decision to separate domain, path, and page analysis into distinct models.

The figure above illustrates the full end-to-end architecture of the phishing detection system as deployed in the Chrome extension. All processing occurs locally on the user’s device. The extension captures the page URL and page content, performs feature extraction for the domain, path, and page content, and feeds each feature set into its corresponding machine learning model. Each model produces an independent score, which is then combined through a weighted ensemble voting mechanism to generate a final phishing confidence score. If this confidence exceeds a predefined threshold, the extension blocks the page and presents a phishing warning along with a context-aware explanation highlighting the most influential features that contributed to the decision. Otherwise, the site is allowed to load normally.

Conclusion

So that was my phishing detection project. I am glad I went deeper than the traditional AI assignment, because it reinforced that machine learning is more than running a prebuilt model on a labeled dataset. Working through real-world issues such as UUID-heavy paths, feature variance, false positives, and deployment constraints pushed me to think more critically about model design and evaluation. This project also led me to better understand how certain features actually influence phishing outcomes in practice, rather than just in theory.

If you would like to read the more technical report we submitted for this project, you can find it here. And if you want to support my work, feel free to drop a like or comment on my LinkedIn post.